It was only after the first few pages of The Land of the Night Sun had already been written that I realised something: it was all in the present tense. But wait, why did I do that?

When writing stories before this one, I had always defaulted to the past tense without question—as probably most of us would. Because that’s how books are supposed to be written, aren’t they? Well, that was the impression I was under. So I backed up before any more damage was done and started rewriting it in the past tense, as I’m supposed to.

Except this time it felt weird, and I couldn’t put my finger on why. Even as I wrote I was often accidentally slipping back into the present tense.

The present tense felt right. But was I wrong for feeling that way?

I stopped what I was doing and decided I ought to look into the matter, in case there were any other writers out there also suffering from a possibly contagious “present tense syndrome”. It seems I’m not alone. In fact, especially among writers of “young adult” fiction the use of the present tense isn’t so uncommon anymore. I admittedly had no idea, especially as I had never encountered it in any book I’ve read—that said, I haven’t consumed much in the way of “young adult” fiction (and I have trouble understanding why such a thing really deserves its own category).

There has also been some backlash against use of the present tense. Philip Pullman, author of His Dark Materials (one of my favourite series), claimed in an article he wrote that it’s all just some silly fad these days to have an “unreliable narrator” and that it’ll pass in time when writers realise they ought to know better. After all, the past tense has served us perfectly well ever since the days our ancestors first gathered around campfires under the stars to listen to tales of brave heroes and terrible monsters. And if it ain’t broke don’t fix it.

Firstly, while we often rely on the past tense to tell a story, I’ve encountered many instances of people recounting a past event in the present tense without having made any conscious decision to do so. It’s a much more casual way of telling it, to be sure—ideal for the sort of story you’d hear over a pint at the pub, for instance. So although the past tense holds the monopoly, it’s never been the only option we have.

As for his argument about the “unreliable narrator”, I fail to understand how the present tense is inherently any less reliable than the past. When you listen to the play-by-play of a football game on the radio, do you really have doubts when a team scores a goal just because the sports commentators didn’t announce it in the past tense? With all due respect, Mr Pullman, I’m not convinced that’s the reason, and while there might have been some bandwagon-hopping involved, I don’t think the growing popularity of the present tense can all be chalked up to a simple urge to be trendy or different either.

On the other end of the spectrum I’ve come across arguments that support its usage, yet frankly I’m not all that convinced by those either. Chief among them is that the present tense feels more, well, tense. Because it gives the illusion that things are happening moment to moment, like one experiences a film, it will make scenes in the story more exciting or suspenseful. I don’t think that’s the case—how exciting or suspenseful a book is will ultimately depend on the skill of the writer, not simply what tense they’ve chosen to use. What can be achieved with one tense can also be achieved with the other, so it seems to be little more than an arbitrary stylistic choice.

Well, maybe that’s not entirely true—I did come across one actual use for it. There are a few chapters in The Jade Necklace that were written in the past tense, particularly stories that are being recounted by other characters to Itzel, and I found being able to switch from the present to the past tense in these situations made it all the clearer that they’re set in the past relative to the story’s main timeline. But those occasional moments aren’t enough to justify almost a whole book being written in the present tense. There’s something more to it.

After giving it some thought I found a possible explanation for why I had unwittingly done it myself: Itzel’s adventure is as much an animated film on paper as it is a book. I put the emphasis on “animated” because there are, of course, countless books that have become films, and many were likely envisioned as such when they were written, and I still would expect very few of them to be written in the present tense. But I have an animation background with years of drawing characters frame-by-frame, and in this case I believe it’s leaked unconsciously into my writing style. The scenes in the books visually play out in my mind as an animated film (complete with its own original soundtrack) and practically every single person who has read them and shared their thoughts with me has specifically mentioned that that’s how they imagine it too. I suspect the use of the present tense plays a large part in that.

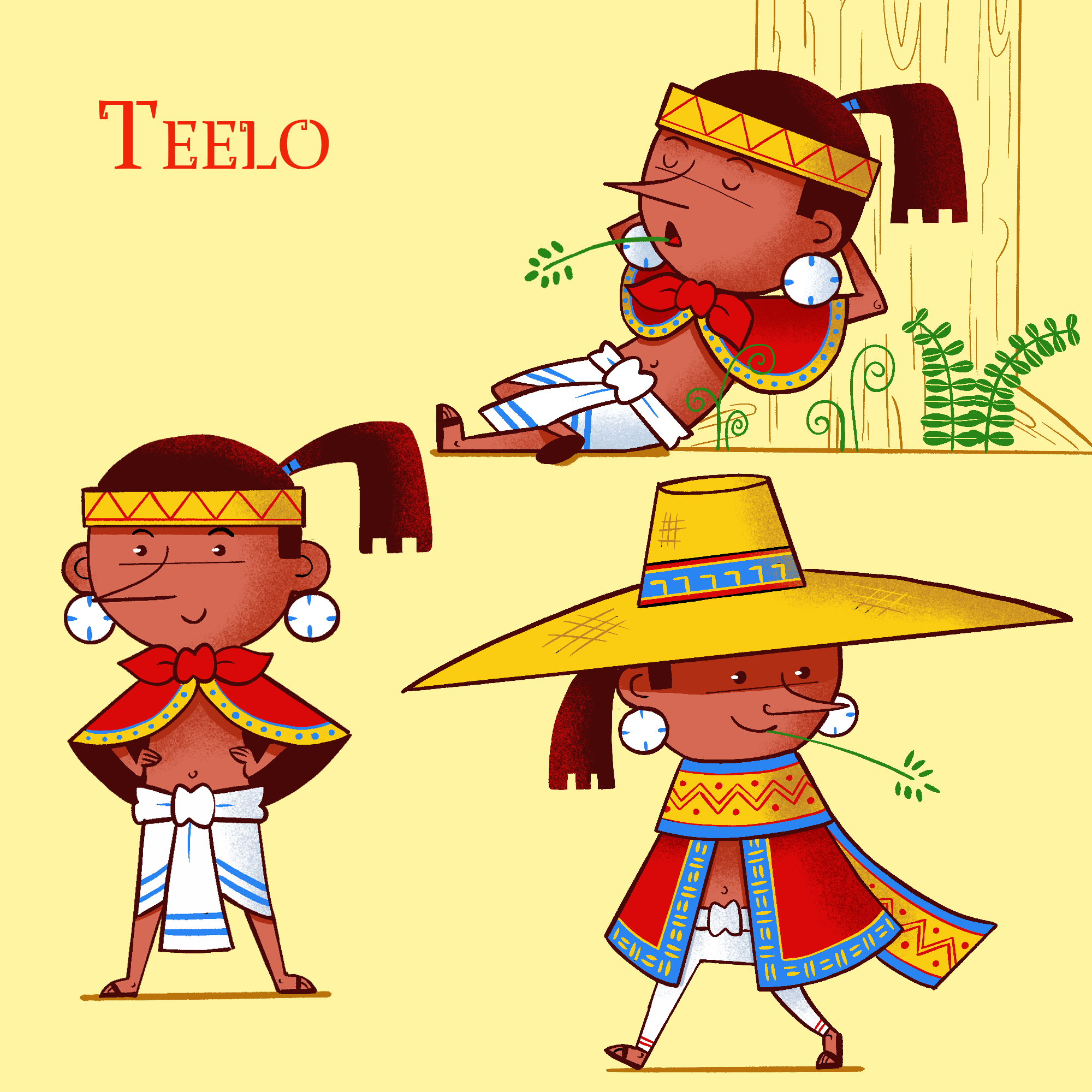

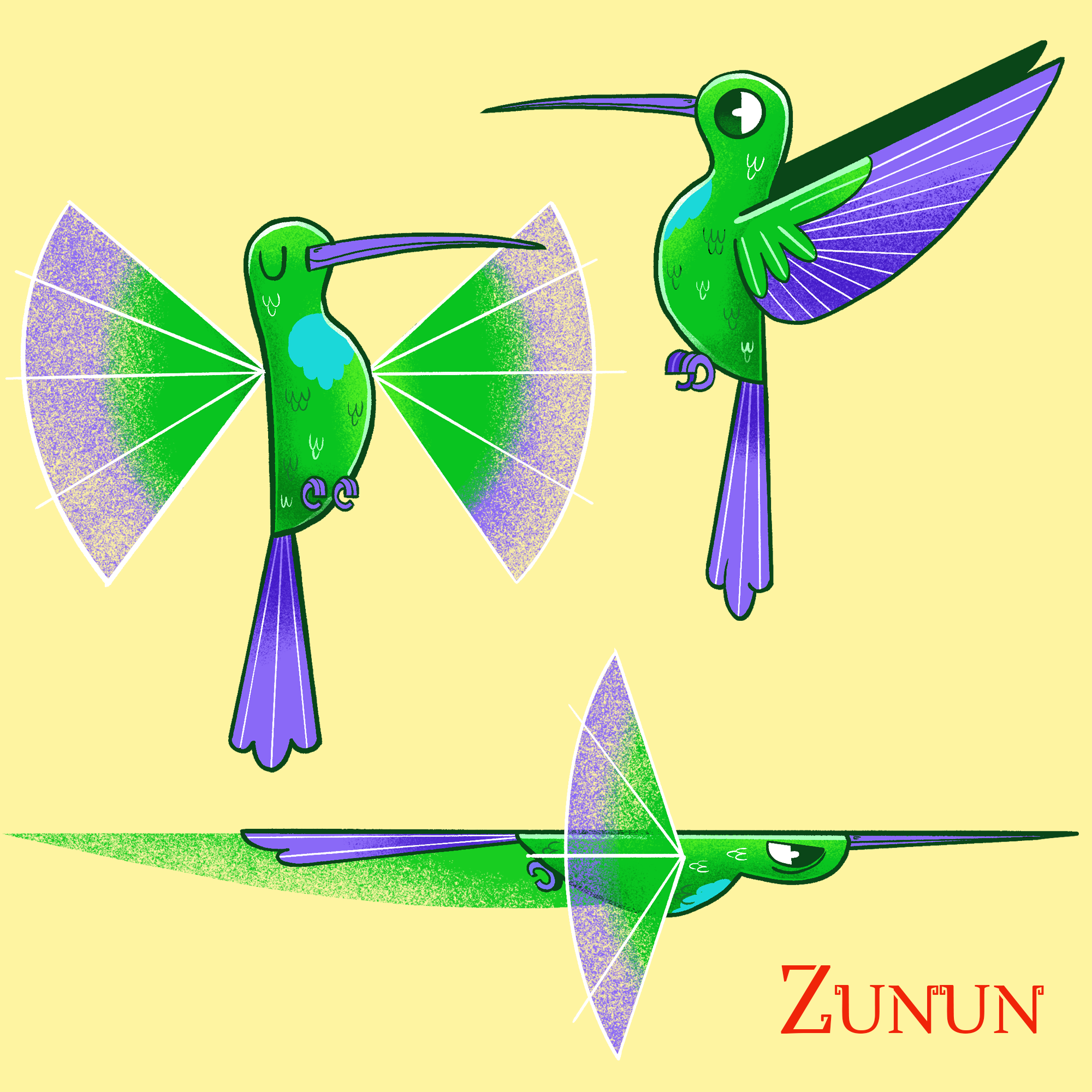

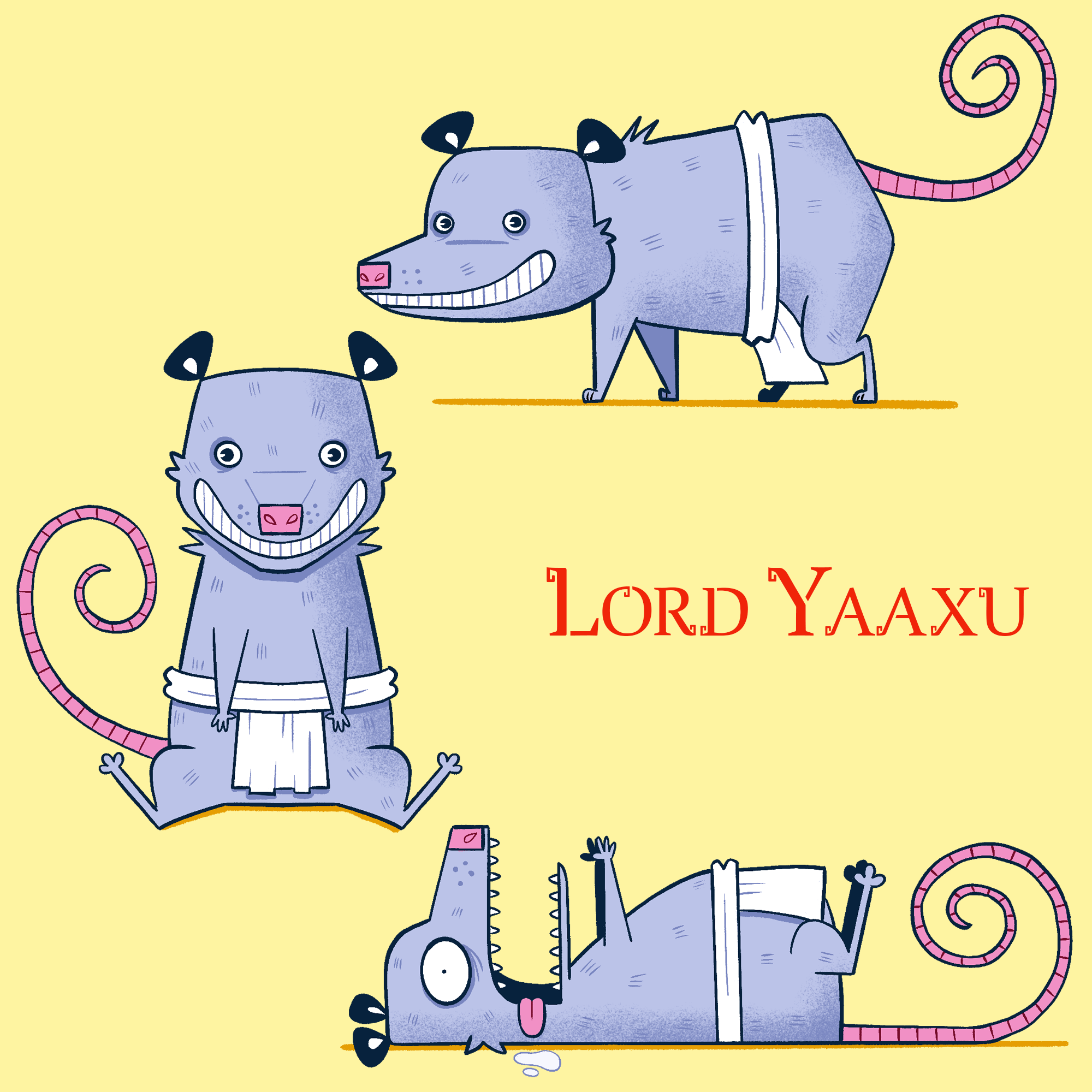

Of course, I have little doubt that it’s also the characters themselves. I imagine Itzel and Quashy just as I draw them—as, and I am hesitant to use this word due to its unfair preconceptions, “cartoons”. In my books there’s no shortage of characters who are completely over-the-top, most of all the gods and animals of Xibalba (there’s even a self-referential joke about it in the second book where Itzel, who has at this point grown accustomed to talking animals, wonders for a brief moment if she’s now in one of her Saturday morning cartoons herself). The cause for my hesitation using the word “cartoon” is that, with the notable exception of Japan where there’s more of a cultural acceptance that manga and anime can be enjoyed by all ages, cartoons are commonly viewed as something that can never be taken seriously, especially by adults. But that’s simply not true (and I think anyone who argues that has clearly never watched Grave of the Fireflies). Though my books are intended as a lighthearted adventure first and foremost, they’re not without their serious moments, and I don’t believe such moments carry any less emotional weight just because they’re enacted by characters who at other times are portrayed as cartoonish.

Some films work better because they’re, well, “cartoons” (a lesson Disney has seemingly forgotten with all their live-action and hyper-realistic CGI remakes—or, much more likely, it’s been intentionally ignored for the sake of more profit). Likewise, The Jade Necklace for me works better as an “animated film in book form” because it was influenced by the classic animated films (from Disney, Don Bluth, Studio Ghibli, et al) just as much as it was by other books, and the present tense was the most suitable way to convey how it unfolded frame-by-frame in my head.

Also, as I said, it felt right. And sometimes you just have to trust your gut.